On a late May morning, with birdsong, boots crunching gravel and a patter of rain on umbrellas replacing the clamour of a busy construction site, trustees from the Sooke School District toured the prefabricated addition going up at David Cameron Elementary in Colwood, B.C.

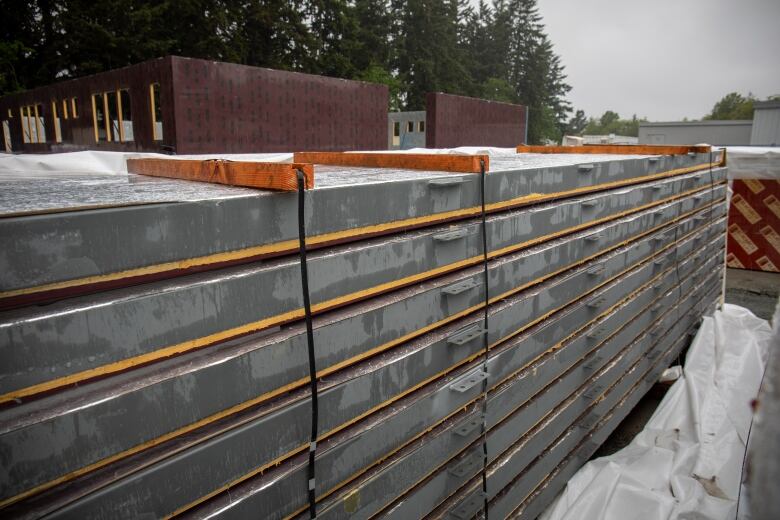

Maroon exterior panels rose over an expansive concrete slab foundation poured just a few weeks earlier. Roof panels — shrink-wrapped and lined up in stacks to the side — would be next, and estimated to take mere days to fasten together.

“It’s kind of a little IKEA … some assembly required,” noted site superintendent Chris Armstrong. “Considerably quicker than a traditional building style, which is part of the appeal, I would say.”

Portable classrooms are common in Canada, a go-to response to student enrolment surges happening across the country. But some jurisdictions are taking modular, prefabricated construction a step further: as a permanent way to address overcapacity challenges.

Proponents see prefab as an ideal way to speed up expansions and new builds. Yet some are concerned if it’s the right solution for schools.

Serving communities west of Victoria targeted as part of a B.C. regional growth strategy, Sooke School District has seen enrolment grow an average of 435 students annually in the last five years alone, said superintendent and CEO Paul Block.

“Essentially an elementary school every single year,” he said.

Sooke’s facilities planners have kept their municipal counterparts, local politicians and B.C.’s Ministry of Education updated on details of that growth throughout, from long-range enrolment projections amid new housing developments to the schools growing most rapidly to the types of buildings required.

Prefabs need to meet ‘same level of quality’

Block says those partnerships helped make Sooke a prime choice for the new prefab initiative B.C. announced last October. Following the announcement, they quickly assembled a project definition report for two elementary school additions, and “by January 2024, we were putting shovels to ground,” he said.

This September, each location will be ready to welcome up to 190 more students.

“So far, all indications are that these prefabs will be the same quality as our regular schools and in fact will be a little bit more up-to-date as well, with modern technology like heat pumps,” said Block.

“[Prefabs] need to be built now and as quickly as possible, but at the same level of quality that a regular build would have,” he said, noting that prefabs can alleviate pressure in schools facing the biggest crunch, while traditional builds can be earmarked for areas seeing slower growth.

Prefab construction isn’t new, but it has resurfaced recently amid discussions of ways to quickly boost Canada’s housing stock. It ranges from buildings comprised of pre-made panels to connecting mostly completed modules to totally finished building units.

In school settings, however, prefab has historically been associated with portable classrooms, which have a reputation for being industrial-looking, feeling too hot or cold and susceptible to problems like poor air quality and mold.

In addition to its celebrated benefit of speedy construction (due to standardized components fabricated in factories), prefab’s come a long way in terms of quality, durability and design, says Mohamed Al-Hussein, professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Alberta.

“The latest technologies I have seen, they are not only high-performance but also resilient … and could stay on as long as the school is there, as long as it’s needed. Some of these classrooms could be there for generations to be used, the way I have seen them built,” said the Edmonton-based modular expert.

Given the improvements in ventilation, insulation, finishing materials, windows, lighting and more, modular prefabricated school buildings “are really no different [from traditional construction] when you’re inside.”

He said important considerations include the current capacity of the prefabrication industry in Canada, the labour that’s required (the people pre-building components as well as the folks assembling them on-site) and high safety standards. Education authorities must also be very clear in communicating to the prefabrication industry what they require.

“I don’t see… any project that cannot have any or some components prefabricated,” Al-Hussein said. “Raise your bar for quality and performance. Industry will react and there is lots of talent out there. The key is to be clear and transparent.”

Care needed amid wide range of prefab offerings

Extremely popular in Sweden, where more than 80 per cent of detached homes feature prefab elements, this off-site construction option is piquing interest elsewhere in Europe, as well as in Asian countries like Japan, China and Singapore, for residences, medical facilities and skyscrapers alike. Australia and the U.K. also have initiatives for prefab in schools specifically.

But a controversy in which several schools in the U.K. built by one contractor were demolished after discovery of structural irregularities and other safety issues highlights the benefit of moving forward with a measured approach.

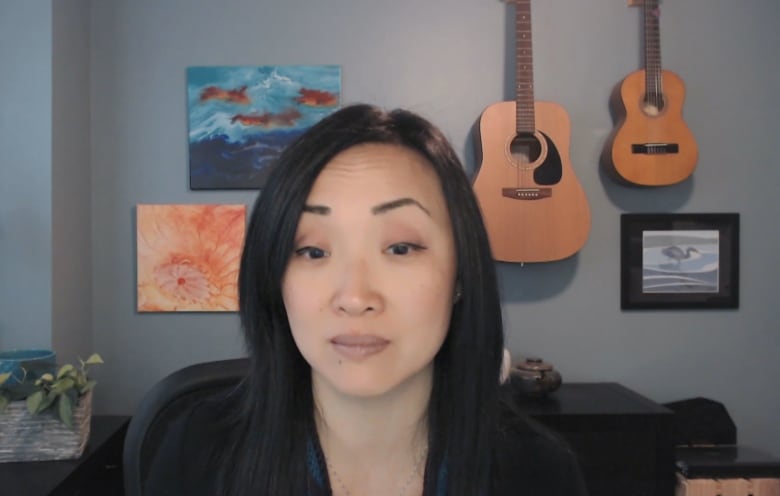

“There really are trade-offs and a wide variety when we think of this idea of prefabrication,” said geography and planning professor Matti Siemiatycki, director of the Infrastructure Institute at the University of Toronto.

Improved designs, speed, cost and environmental considerations are among possible benefits to prefabricated construction in school settings, but other factors must be considered as well, says professor Matti Siemiatycki, director of the Infrastructure Institute at the University of Toronto.

He said prefab school buildings can be beautifully designed, more environmentally friendly and energy efficient than traditional builds and can be quickly and cost-effectively erected — or they may not be, due to the wide range of modular construction that exists.

“We should be trying to invest not just in the systems, but also in the designs and the architecture to make sure that these do become great spaces that are bright, that are well-ventilated, that have the heating and cooling systems, that have safe washrooms, everything that makes for a good learning environment.”

Along with careful review of prefab manufacturers and suppliers and how their buildings have aged, Siemiatycki thinks education authorities must also pay attention to maintenance.

“In Canada, we spend a lot of time thinking about how we’re going to build new infrastructure, and then we take our eye off the ball,” he said. “Regardless of whether it’s traditional build or prefabricated, we have to be investing in the ongoing operations. Everything gets old, time doesn’t stand still, things wear and tear.”

More than just classrooms needed, says parent

In Surrey, B.C. — which is also challenged by over-capacity schools — some parents are concerned that while prefab goes up faster than a traditionally built school, kids might still get the short end of the stick.

“Modulars are wonderful in that they cut down the time to build a school, but it doesn’t increase the [size of the] gym, it doesn’t increase the library or any of the resource areas,” noted Anne Whitmore, a parent of three elementary students in the Surrey School District.

WATCH | Take a peek at what the prefab David Cameron Elementary addition will look like:

If separated from the main school building, kids in additions must gear up in cold or rainy weather to access central resources like the library, music or gym classes or to attend school assemblies. Modular additions also eat up existing field or playground space, Whitmore said.

“It’s not so much like [everything] has to be a brick-and-mortar school, but schools are well-rounded centres. So when we start adding and not really building out a school to be resourced for the amount of children that are in it, we’re doing a disservice, and we’re calling it education.”

Back on Vancouver Island, Block emphasized that Sooke has set clear design standards for the modern learning spaces its students need (“not just rectangular boxes”) for both additions and new schools, prefab and traditionally built.

“What’s the best learning environment for our kids?… It’s not just about quick buildings, but it’s also building the right kind of building,” Block said. “Not just for 2024, but also for 2050 and beyond.”