A northern Alberta woman is hoping her family’s history can help reunite other families with loved ones laid to rest far from home.

In 2019, Shannon Cornelsen was handed a box of her grandfather’s journals documenting his time as an Indian Affairs agent

Norman McGinnis was famous in his family for being a devoted notetaker, filling 27 books with the details of his workdays at the Stony Plain Indian Reservation (now Enoch Cree Nation) between 1954 and 1980.

Entries offer a look at where he went and why he was there, if it was sunny or snowing, and how much he spent on lunch and other expenses – including a $1 dinner in Lac St. Anne on April 23, 1958.

“But it was not that content that I was interested in,” Cornelsen said. “It was the fact that he detailed the burials of patients from the Charles Camsell Indian hospital.”

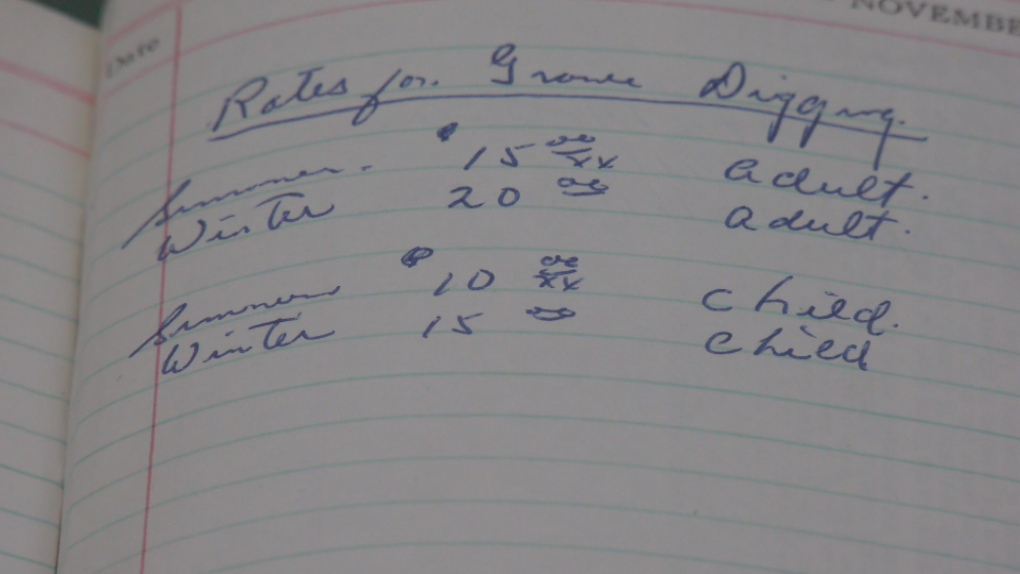

An entry in Shannon Cornelsen’s grandfathers journal, showing the rates to dig a grave for patients of the Charles Camsell Indian hospital in Edmonton who died and were not returned home for burial. (Nahreman Issa/CTV News Edmonton)The hospital, located on what is now 128 Street and 114 Avenue in Edmonton, was the largest facility run by federal Indian Health Services between 1946 and 1980.

An entry in Shannon Cornelsen’s grandfathers journal, showing the rates to dig a grave for patients of the Charles Camsell Indian hospital in Edmonton who died and were not returned home for burial. (Nahreman Issa/CTV News Edmonton)The hospital, located on what is now 128 Street and 114 Avenue in Edmonton, was the largest facility run by federal Indian Health Services between 1946 and 1980.

First Nation and Inuit patients were taken there, in part for tuberculosis treatments, from communities around Alberta, northern British Columbia, the Yukon and the Northwest Territories.

Many of them would never return home. Cornselson wants to change that.

Forty-nine names

The names in those old notebooks represent people who died at the Camsell hospital but were never reunited with loved ones.

Cornselson said that’s due to a federal policy from 1947, requiring that patients who died there – but who were not claimed by family – would be buried at the Enoch Cree Nation cemetery.

“We need to reconnect these families with the burial places of their loved ones,” she said.

“Closure is something that we all deserve, and I feel that Indigenous people across Canada from residential schools and from the segregated Indian Health Care system have not always received that kind of closure.”

To aid in her mission, Cornelsen enrolled in Native Studies at the University of Alberta the year after she was given the journals.

“I started university at the age of 50 years old,” she said. “To gain the skills and the knowledge so that I can do this research properly.”

Not every entry has a name, but Cornelsen has been able to find leads in the death records at the provincial archive.

“I’m able to search for the specific dates and hopefully match up specific information,” she said. “At this point, I need to pull all of the death certificates and certify them against the Indian register in Ottawa in the National Archives.”

Cornelsen said she’s found more than 50 more names in the archive, and she expects to encounter many more before she’s done.

It’s a lot of work, but she feels answers are owed and she wants to help find them.

“I don’t think it’s human how people were able to be removed from their homes and from their communities and never be seen again,” she said. ‘”To never have your family members know where you ended up, that uncertainty would just be heartbreaking.

“So I feel a deep responsibility to make sure that those families get reunited with where their loved ones are.”

Reconciliation

Cornelsen is from Saddle Lake Cree Nation, and her mother Lydia Cardinal – who recently celebrated her 87th birthday – was taken to the Blue Quills Residential School when she was five years old.

The Acimowin Opaspiw Society (AOS), in 2022, said it had found documents for 215 students at Blue Quills who died between the age of six and 11, but whose remains were unaccounted for.

In 2023, the AOS released details of a report it says uncovered physical and documented evidence regarding the mass burial of children who attended the Blue Quill school.

During her 10 years at Blue Quills, Cornelsen said her mother endured “enormous” abuse.

It’s just one part of her family’s story, but it’s a big part of what drives her work, which she plans to continue during her master’s degree after she graduates this year.

“It’s so imperative to me that people understand what truth and reconciliation is and the different steps that we can all take to move forward,” Cornelsen said.

“It’s important to tell these stories, and it’s important to keep this information out in the media and out in public,” she added. “The more that we can do to help reconcile with Indigenous communities, the better Canada is going to be.”

Shannon Cornelsen’s parents, Bert McGinnis and Lydia Cardinal, can be seen on their wedding day in 1969. (Supplied)A class-action lawsuit was filed against the Attorney General of Canada in 2019 over the management of IHS hospitals, originating from a woman who was a patient at the Camsell Hospital in 1969.

Shannon Cornelsen’s parents, Bert McGinnis and Lydia Cardinal, can be seen on their wedding day in 1969. (Supplied)A class-action lawsuit was filed against the Attorney General of Canada in 2019 over the management of IHS hospitals, originating from a woman who was a patient at the Camsell Hospital in 1969.

The most recent statement of claim states she, and other defendants, experienced system abuse including forced confinement, assault, and sexual and psychological abuse.

None of the allegations have yet been proven in court.

In 2021, the Camsell hospital grounds were searched for unmarked graves after ground-penetrating radar showed “anomilies” on the site.

None were found, and the hospital building is now being redeveloped into condos

If you are a former residential school student in distress, or have been affected by the residential school system and need help, you can contact the 24-hour Indian Residential Schools Crisis Line at 1-866-925-4419, or the Indian Residential School Survivors Society toll-free line at 1-800-721-0066.

Additional mental-health support and resources are available here.

With files from CTV News Edmonton’s Nahreman Issa and Sean Amato